Hepatorenal syndrome

At a Glance

How It Affects You

Hepatorenal syndrome is a life-threatening type of kidney failure that occurs in people with severe liver disease, caused by changes in blood flow rather than direct damage to the kidneys. As the liver fails, blood vessels in the gut widen while vessels in the kidneys constrict, drastically reducing blood supply to the kidneys and impairing their ability to filter waste. This leads to a rapid accumulation of toxins and fluid in the body.

Key effects include:

- Significant decrease in urine production and buildup of waste products in the blood (azotemia).

- Worsening fluid retention in the abdomen (ascites) and swelling in the legs.

- Confusion or cognitive impairment due to the liver's inability to clear toxins.

Causes and Risk Factors

Underlying Causes

Hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) is caused by a chain reaction starting with severe liver disease, typically cirrhosis. As the liver creates resistance to blood flow (portal hypertension), blood vessels in the splanchnic (gut) circulation widen excessively. To maintain blood pressure, the body releases hormones that constrict blood vessels elsewhere. Unfortunately, this causes severe constriction of the blood vessels leading to the kidneys. The kidneys themselves are usually structurally normal but stop working because they are starved of blood flow.

Risk Factors and Triggers

While advanced liver disease is the primary prerequisite, specific events can trigger the onset of HRS. A major trigger is spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), an infection of the fluid in the abdomen. Other risk factors include gastrointestinal bleeding, excessive use of diuretic medications (water pills), severe dehydration from diarrhea or vomiting, and large-volume paracentesis (draining fluid from the abdomen) without administering albumin replacement.

Prevention

Primary prevention focuses on managing the underlying liver disease to prevent decompensation. Strategies include preventing infections with antibiotics in high-risk patients and carefully managing diuretic dosages. For patients undergoing large-volume paracentesis, the administration of albumin is a critical preventive measure to maintain blood volume and prevent kidney constriction. There are no vaccines specifically for HRS, but vaccines for hepatitis A and B are important for overall liver health.

Diagnosis, Signs, and Symptoms

Signs and Symptoms

Symptoms of hepatorenal syndrome often overlap with those of liver failure. The most clinically meaningful sign is a sharp decrease in urine output (oliguria) and very dark, concentrated urine. Patients typically experience worsening accumulation of fluid in the abdomen (ascites) and swelling in the legs (edema). As waste products build up, patients may develop nausea, vomiting, weakness, and confusion or drowsiness (hepatic encephalopathy). In the rapid form of the disease, these symptoms develop over days or weeks.

Diagnostic Process

There is no single specific test for HRS; it is a diagnosis of exclusion. Clinicians diagnose it by identifying kidney failure in a patient with advanced liver disease and ruling out other causes. Key diagnostic criteria include elevated serum creatinine levels (indicating poor kidney function) that do not improve after stopping diuretics and giving fluids (albumin) for two days. Urine analysis is used to show that the kidneys are holding onto sodium avidly (low urine sodium) and that there is no protein or blood indicating structural kidney disease. Ultrasound imaging is often performed to ensure there are no blockages or physical damage to the kidneys.

Differential Diagnosis

Doctors must distinguish HRS from other causes of acute kidney injury. This includes dehydration (prerenal azotemia) which responds to fluids, acute tubular necrosis (damage from toxins or shock), and drug-induced kidney injury (such as from NSAIDs or antibiotics). Differentiating these is crucial because the treatments differ significantly.

Treatment and Management

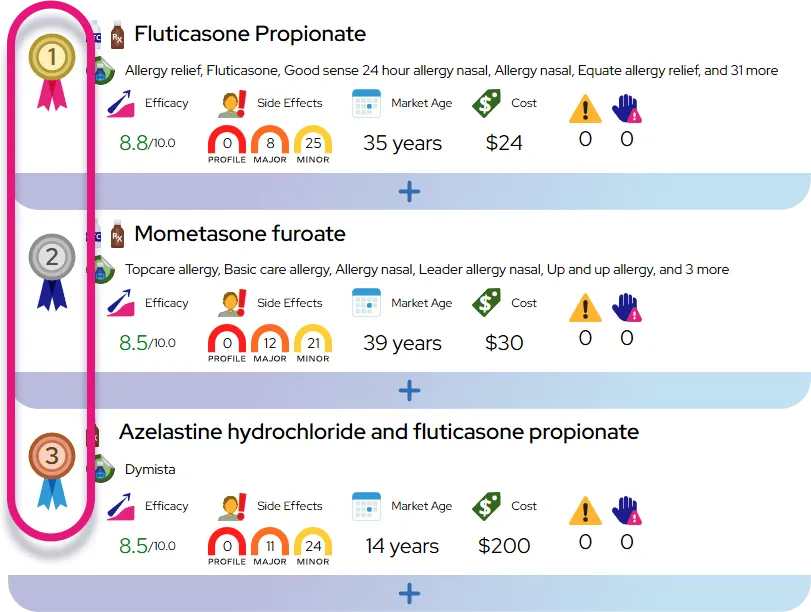

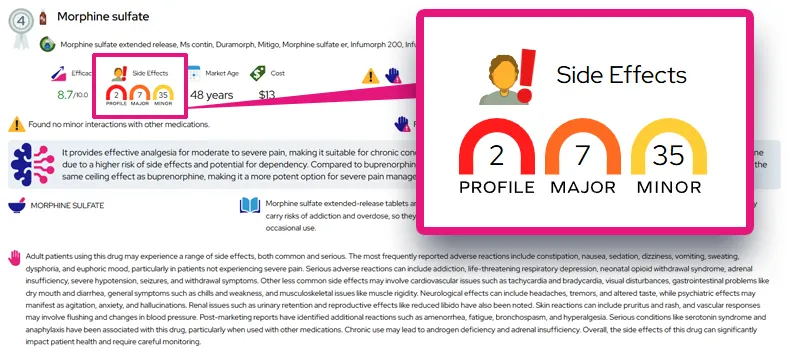

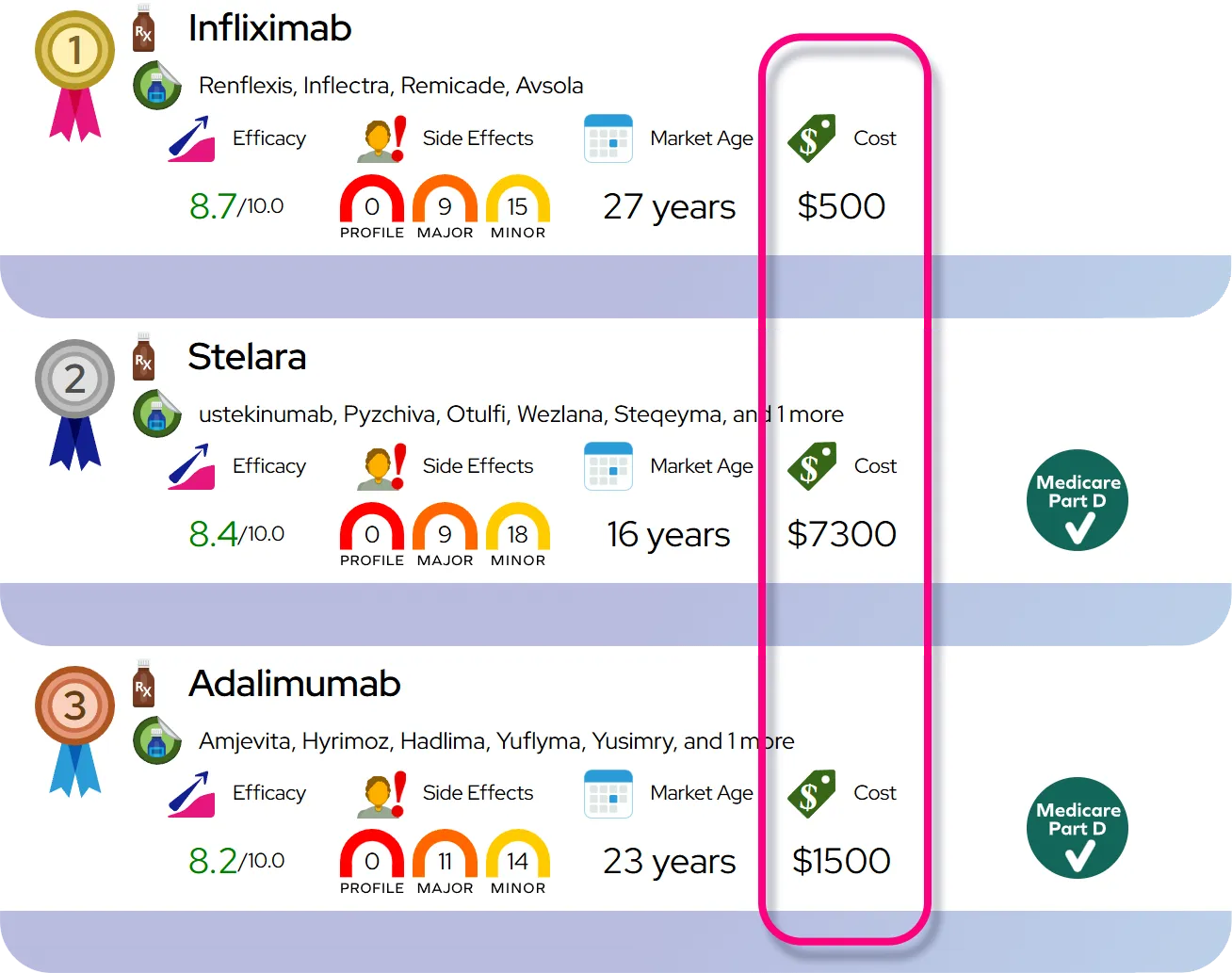

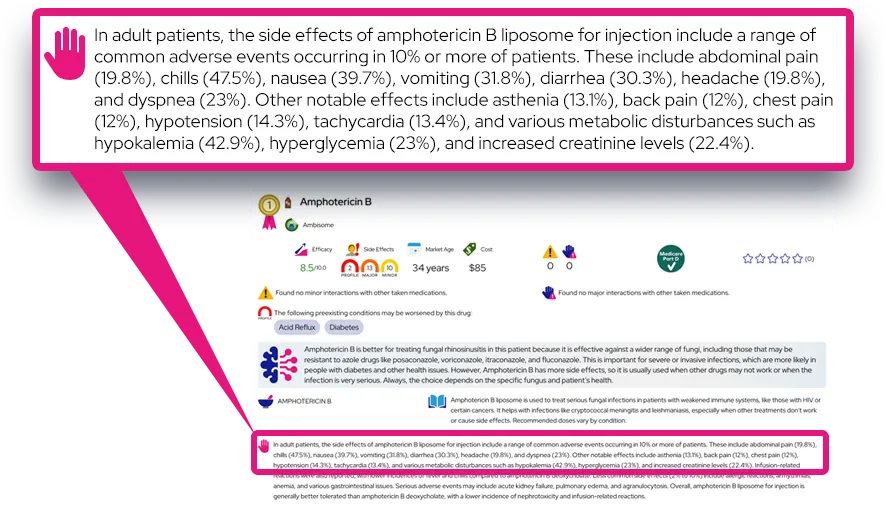

Medications

The first line of treatment involves medications to constrict the widened blood vessels in the gut, thereby redirecting blood flow back to the kidneys. Common drugs include terlipressin (where available), norepinephrine (in intensive care), or a combination of midodrine and octreotide. These are almost always given alongside intravenous albumin to increase blood volume. This combination can reverse kidney failure in a significant number of patients, acting as a bridge to other treatments.

Procedures and Surgery

For patients who do not respond to medication, a Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt (TIPS) may be considered to reduce pressure in the liver, though it carries risks. Renal replacement therapy (dialysis) may be used to filter the blood if the kidneys completely fail, but it is typically only used if a patient is a candidate for liver transplantation. The only definitive cure for hepatorenal syndrome is a liver transplant. In some cases, a combined liver-kidney transplant is performed, especially if the kidney failure has lasted a long time.

Management and Lifestyle

Management takes place in a hospital setting. Doctors will discontinue any medications that could harm the kidneys, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and certain blood pressure medicines. Diuretics are usually stopped temporarily. Fluid intake and urine output are monitored hourly. Lifestyle changes are limited to the post-recovery or transplant phase, focusing on diet and alcohol cessation.

When to Seek Medical Care

Patients with cirrhosis must seek emergency care immediately if they notice a sudden drop in urine output, dark or tea-colored urine, new or worsening confusion, or signs of infection such as fever or abdominal pain. Routine follow-up is essential for anyone with cirrhosis to monitor kidney function (creatinine) and electrolytes.

Severity and Prognosis

Severity and Classifications

Hepatorenal syndrome is a severe, life-threatening condition. It is historically classified into two types, though newer guidelines refer to them as HRS-AKI (Acute Kidney Injury) and HRS-NAKI (Non-AKI). HRS-AKI (formerly Type 1) is the rapid and more severe form where kidney function collapses within two weeks. HRS-NAKI (formerly Type 2) progresses more slowly and is typically associated with fluid retention that does not respond to diuretics (refractory ascites).

Prognosis and Survival

Without treatment, the prognosis for HRS-AKI is extremely poor, with a median survival of only a few weeks. Most patients do not survive more than a few months without a liver transplant. However, modern drug therapies can reverse the condition in about 40-50% of cases, significantly improving short-term survival and allowing time for a transplant evaluation. The long-term outlook is excellent for patients who successfully undergo liver transplantation, as the new liver restores normal blood flow and kidney function often recovers.

Complications

Complications include severe electrolyte imbalances (high potassium), fluid overload leading to heart/lung strain, and worsening brain function (coma) due to the buildup of toxins. If the kidneys remain shut down for too long (usually over 4-6 weeks), they may sustain permanent structural damage, necessitating a kidney transplant alongside the liver transplant.

Impact on Daily Life

Impact on Daily Life

Patients with active hepatorenal syndrome are typically too ill to work or attend school and usually require hospitalization, often in an intensive care unit. The condition imposes severe physical limitations due to weakness, massive fluid retention, and confusion. For those with the slower-progressing form (Type 2/HRS-NAKI), daily life revolves around managing ascites, frequent doctors' visits, and strict dietary restrictions (low sodium). The emotional toll is significant for both patients and families due to the critical nature of the diagnosis and the uncertainty regarding transplant eligibility.

Questions to Ask Your Healthcare Provider

Patients and caregivers should ask specific questions to understand the situation:

- Is this the rapid form (HRS-AKI) or the slower form of the syndrome?

- Am I (or is the patient) a candidate for a liver transplant?

- What specific medications (like NSAIDs) must be strictly avoided?

- What are the signs that the treatment is working or failing?

- Is dialysis recommended as a bridge to transplant in my case?

Common Questions and Answers

Q: Is hepatorenal syndrome reversible?

A: Yes, it can be reversible. About half of patients respond to drug therapy (vasoconstrictors and albumin), which can restore kidney function. However, the most permanent reversal comes from liver transplantation, which fixes the underlying circulatory problem.

Q: Can the kidneys recover after a liver transplant?

A: In many cases, yes. Since the kidneys in HRS are usually structurally normal, they often resume normal function once a healthy liver restores proper blood flow. If the kidney failure has lasted a long time, however, the damage may become permanent.

Q: Is hepatorenal syndrome painful?

A: The kidney failure itself is not typically painful, but the associated conditions can be uncomfortable. Patients often experience significant discomfort from the distension of the abdomen due to fluid buildup (ascites) and may have muscle cramps.

Q: How does it differ from other types of kidney failure?

A: Unlike most kidney failure which is caused by damage to the kidney tissue (like from diabetes or high blood pressure), HRS is "functional." This means the kidneys are healthy but are failing because severe liver disease has disrupted the blood flow they need to operate.

Q: Can diet heal hepatorenal syndrome?

A: No, diet alone cannot cure HRS. However, a low-sodium diet is crucial for managing the fluid retention associated with the underlying liver disease. Nutritional support is important as many patients are malnourished, but medical intervention is required to treat the syndrome.